The eagerly awaited Performance Report of the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) for 2024 has recently been published. It offers some context regarding the IRD’s tax collections. There is room for wider disclosure that would improve transparency. The timeliness of the report’s release could also be considerably enhanced. After all, most large corporations listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange publish their Annual Reports within two months of the financial year’s end.

Sri Lanka’s fiscal challenges remain pressing, despite the strong headline growth in Inland Revenue Department (IRD) collections for 2024. The performance report shows an impressive 44% increase in collections, reaching Rs. 2.6 trillion compared to Rs. 1.8 trillion in 2023.

However, this growth has been heavily skewed towards indirect taxes, particularly Value Added Tax (VAT), whose collections increased by nearly 89%. The structural imbalance between direct and indirect taxes has widened once again, with the ratio shifting from 50:50 in 2023 to 40:60 in 2024.

While VAT reforms, including higher rates and lower registration thresholds, have expanded collections, income tax performance remains weak. The Rs. 1 trillion collected from income taxes conceals significant inequities: fewer than 1 million individuals out of a workforce of over 8 million are within the tax net, and a very small segment of high-income earners shoulder a disproportionate share of the personal income tax burden. This situation is both socially and economically unsustainable.

Recent reports, including the World Bank’s Public Finance Review and commentary from international experts such as Professor Mick Moore, highlight systemic weaknesses in Sri Lanka’s tax administration. Outdated methods, inadequate human resource planning, and governance failures at the IRD undermine enforcement and modernization. Structural reforms, particularly digitization, improved compliance enforcement, and the recruitment of skilled professionals, are essential to move away from reliance on regressive indirect taxation.

Revenue Performance: Headline Gains but Fragile Foundations

The IRD’s collection of Rs. 2.6 trillion in 2024 is unprecedented in nominal terms. VAT alone contributed an additional Rs. 615 billion, nearly doubling year-on-year. This sharp increase is attributable to two main factors: the rate hike, which saw VAT increase to 18% from 15%. – Wider base: The registration threshold was reduced from Rs. 80 million to Rs. 60 million annually, pushing the number of VAT-registered establishments to 21,227—a 53% increase.

However, reliance on VAT has shifted the tax mix towards indirect taxes. The direct-to-indirect ratio dropped back to 40:60, weakening equity. Indirect taxes, by their nature, impact lower-income households more heavily, increasing inequality.

In contrast, income tax collections reached Rs. 1 trillion in 2024—a modest 13% increase from the previous year. Given the urgent need to expand the tax base, this figure highlights the limited success of enforcement and compliance efforts.

Who Pays Income Tax?

Income tax collections reveal the narrowness and inequities of Sri Lanka’s direct tax base:

– Corporate income tax, Rs. 582 billion, from 100,049 companies. The collection represents an increase of 5% over 2023.

– Personal and partnership income tax: Rs. 442 billion from 976,498 individuals and 16,227 partnerships. The collection represents an increase of 26% over 2023.

In the year 456,035 new taxpayers were added to the tax base (mostly individuals). However, the report fails to disclose how much additional revenue these new taxpayers contributed. Such disclosure would improve transparency and might also help dispel the feeling that the IRD is squeezing the same lemon!

Similarly, revealing how many of the registered companies actually pay income tax would promote greater transparency.

The Rs. 442 billion collected as personal income tax has been broken down as follows:

Advance Personal Income Tax (APIT) – private sector employees: Rs. 198 billion.

Advance Income Tax on bank interest payments: Rs. 66 billion.

Advance Income Tax from specified fees and others: Rs. 98 billion.

The APIT collection from private sector employees increased by Rs. 53 billion in 2023, representing a 36% rise. There is a shortfall of Rs. 81 billion in Non-Corporate Income Tax that I could not find in the report.

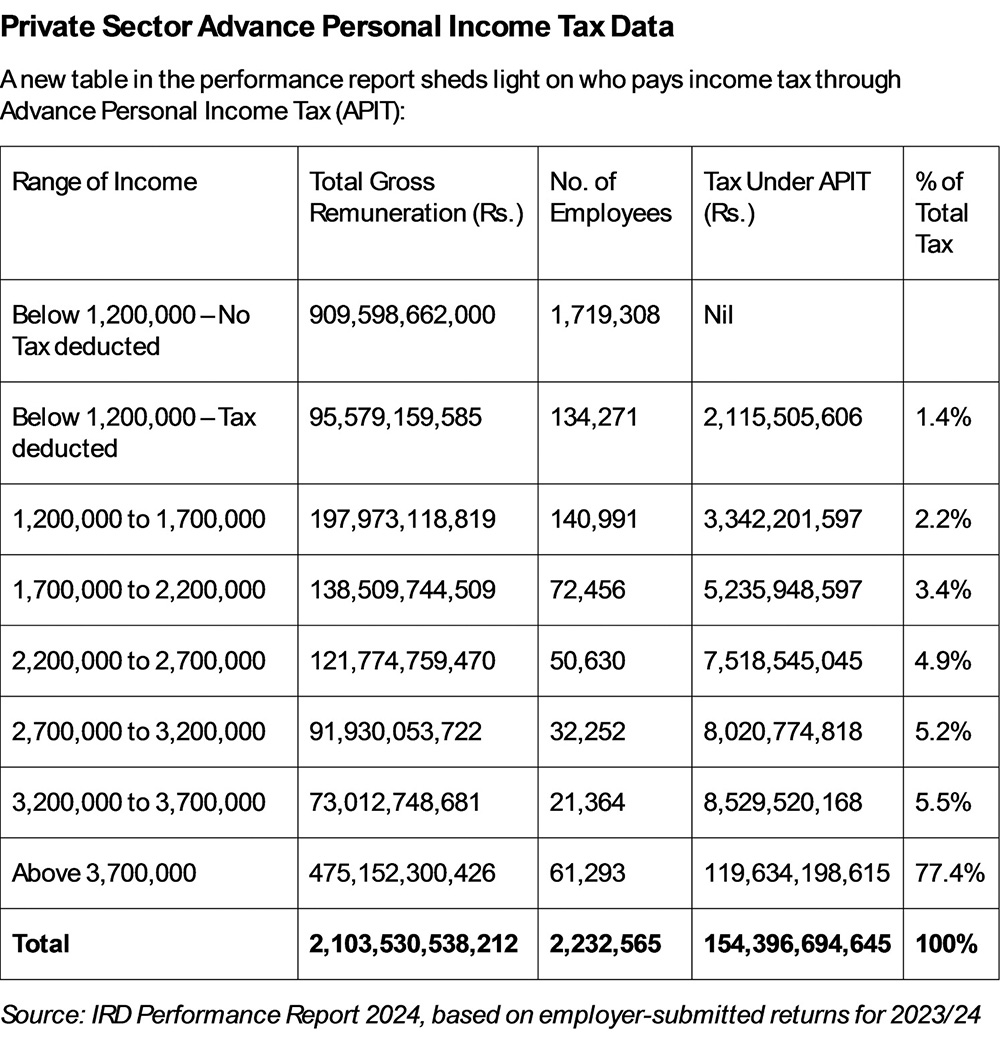

Private Sector Advance Personal Income Tax Data

A new table in the performance report sheds light on who pays income tax through Advance Personal Income Tax (APIT):

This table highlights three key issues: – Even in the formal private sector, 77% of employees pay no income tax as their earnings fall below the income tax-free threshold. – A very small group (61,293 individuals) accounts for over three-quarters of APIT paid.

With the 2025 increase in the tax-free threshold to Rs. 1.8 million, around 275,000 employees will exit the tax net, further narrowing the base.

Tax Return Compliance

It is compulsory for those liable to income tax to submit a tax return by 30th November following the end of the tax year, detailing their income for the year, as well as assets owned, and liabilities owed. According to the IRD, very few companies and individuals submit their returns on time.

Only the large Corporate Taxpayers, numbering 621, achieved a 93% compliance rate. Of the remaining 91,183 companies, only 26,241 submitted their returns on time, which corresponds to a compliance rate of 29%.

The compliance rate among individual taxpayers is also very poor, with only 110,240 out of 792,530 submitting their returns on time, resulting in a compliance rate of just 24%.

Failing to submit tax returns on time does not necessarily mean taxpayers are evading taxes, but assuming so is reasonable.

World Bank’s Public Finance Review 2025

The World Bank’s Report Towards a Balanced Fiscal Adjustment highlights the fragility of Sri Lanka’s revenue model: – 75% of revenue gains since 2022 came from indirect taxes (VAT, SSCL, excise duties). – Regressive impact: VAT consumes 5.3% of pre-fiscal income for the poorest decile, compared to 3.3% for the richest. – Poverty impact: The 2024 VAT hike alone increased poverty by 2.2 percentage points. – Sustainability concerns: Reliance on indirect taxation is not only socially unjust but also economically unsustainable.

The report calls for digitization and comprehensive reform of the IRD, emphasizing the need for better sequencing, resourcing, and HR capability development. It also warns against the “easy option” of squeezing a narrow taxpayer base, urging policymakers to prioritize compliance enforcement and structural reforms.

Professor Moore’s Perspective: 20 Years Behind many African Countries

Professor Mick Moore, a leading political economist on taxation, argues that Sri Lanka’s IRD is as outdated as its Customs Department—lagging 20 years behind even many African peers. He highlights systemic failures: – Low compliance: e.g., only 20,000 of 110,000 businesses in Colombo pay local property tax. – Outdated practices: reliance on manual processes and weak data integration. – Poor HR systems: lack of skilled recruits, minimal training, and outdated promotion practices.

Moore stresses that enforcement should target large businesses and high-value taxpayers, rather than informal operators. He says that without skilled staff, modern audits, and investment in IT/data analytics, Sri Lanka cannot close its revenue gap.

Human Resource and Institutional Challenges

The IRD’s own performance report presents a grim view of institutional capacity: – Approved cadre: 1,639 officers. – Vacancies: 227 (14%). – Ageing workforce: 33% of staff are aged 51–60, with most serving over 15 years. – Promotion bottlenecks: Dozens of senior positions remain in “acting” status due to Public Service Commission delays, causing staff dissatisfaction and demotivation.

Compounding the problem, earlier officer-level recruitment was halted by trade union pressure, resulting in the discontinuation of the Tax Officer and Assessor posts. New recruits are now directly appointed as Assistant or Deputy Commissioners, roles that were previously reserved for experienced officers. This undermines institutional knowledge and succession planning. I understand that between 2007 and 2017, there was no recruitment to the officer cadre.

The lack of skilled professionals in IT, data science, and financial analysis has left the IRD unprepared for digitisation and modern enforcement.

Policy Implications and Reform Agenda

Sri Lanka cannot rely solely on rate hikes and regressive indirect taxes to fund its budget. The IRD’s weaknesses demand urgent reform. Some of the key initiatives identified by agencies and experts include:

· Digitisation and Data Integration

· Build a modern, unified tax administration platform integrating VAT, income, excise, and customs data.

· Use third-party data (banks, utilities, property registries, travel agents) to cross-check declarations and expand the net.

· Broadening the Tax Base

· Enforce compliance among high-income professionals and self-employed groups who are currently under-reporting.

· Strengthen property taxation, aligning municipal and IRD databases.

· Human Resource Overhaul

· Recruit IT specialists, data analysts, and forensic accountants.

· Reform promotions to be performance-based rather than seniority-based.

· Resolve acting appointments to restore morale and accountability.

· Targeted Enforcement

· Prioritize audits on large businesses, high-net-worth individuals, and multinational corporations.

· Avoid excessive focus on small informal operators, who contribute little revenue but face disproportionate harassment.

· Institutional Independence and Governance

· Strengthen the autonomy of the IRD to shield it from political interference.

· Ensure stable leadership and merit-based recruitment.

Conclusion

The 2024 IRD performance report highlights both achievements and vulnerabilities. The revenue increase of Rs. 800 billion over 2023 is genuine but relies heavily on regressive VAT hikes, rather than on structural reforms or a broader tax base. Income tax remains underdeveloped, with fewer than 12% of the workforce contributing directly. The result is a narrow and inequitable system that discourages compliance, undermines social fairness, and hampers long-term growth.

The World Bank and experts like Professor Moore deliver a clear warning: Sri Lanka’s tax administration is outdated, under-skilled, and politically ignored. Without urgent reforms—such as digitization, enforcement of compliance, HR renewal, and governance restructuring—the state will keep squeezing a small pool of taxpayers while leaving most outside the net.

Previous governments’ failure to strengthen the IRD has cost the country dearly in lost revenue and fiscal instability. The task now is to develop and implement reforms that are both technically sound and politically viable. A better tax system is crucial for building public trust, reducing inequality, and boosting Sri Lanka’s economy.

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera